The Recruitment-Confusion-Matrix and your Right to be Wrong

posted on 22 Jul 2020

In this article I want to elaborate on a reality in recruitment, which is often left out of the conversation, but actually makes up the biggest chunk of our work. I want to talk about wrong decisions, specifically from a recruiter’s perspective. As a matter of fact, as a recruiter, you are more often wrong than you a right. Numbers don’t lie. So don’t trust your gut feeling!

Since decision making in recruitment is a form of statistical classification, a confusion-matrix seems to me very suitable to lay out the challenge. Towards the end of this article, I want to share some tips for recruiters, but also for all hiring team member’s what can be done to increase screening quality and efficiency, especially in the early stage of the recruitment process. But first, let’s start with some Numbers and KPI-Benchmarks:

Lever’s 20l9 Talent Benchmark Report looked at the recruiting efficiency of around 2500 companies. For software engineering positions, the conversation rates look the following.

-

The average screen-to-onsite conversion-rate is 23,57%.

-

The average onsite-to-offer conversion-rate is 34,93%.

-

The average offer acceptance conversion-rate is 58,46%.

The numbers for Data and Design positions look similar. Since we are talking here about averages, it can be assumed that the conversions are higher for easier positions and lower for more difficult positions. So it’s reasonable to assume that for a significant chunk of important and challenging roles, the conversion rates are even lower.

That means, in average, 1 out of 3 candidates screened and forwarded by the recruiter will receive an offer (onsite-to-offer rate). And just 1 out of 5 candidates screened and forwarded by the recruiter will get hired.

That means also, at least 2 out of 3 times, the recruiter made the wrong call. And if we decide based on who gets hired or not, even 4 out of 5 times the recruiter made the wrong call.

A Recruiter’s Prediction

Like any other skill, the craft of recruiting can be trained, sharpened and polished through repetition. As a recruiter, your job is basically to evaluate skills and make predictions. A recruiter predicts whether there is a high chance that …

-

The candidate fulfills the requirements of the vacant role AND

-

The role, the team and the whole company can offer a fulfilling challenge and environment for the candidate AND

-

There is a high chance both parties can come together on contractual conditions and other requirements like salary, other forms of financial rewards or equity, travelling etc.

But since no one can not predict the outcome with full certainty, the recruiter’s decision is more a bet than a certain prediction.

Because making these bets are the recruiter’s profession, one could assume that the recruiter’s judgement must be of high accuracy. And indeed, an experienced recruiter already facilitated hundreds, maybe thousands of candidate journeys in different constellations and contexts and saw how different things played out. Because of the high volume and relatively fast feedback cycles, the recruiters working environment definitely allows the development of a somewhat reliable intuition. But whenever we are operating within the field of human beings and decision making, biases, inaccuracies and wrong decisions are inevitable.

Three main Parts of the Process

For the sake of simplification, Lever divided and summarised the recruitment process into two steps, ‘screening’ and ‘onsite-interview’. Within the onsite-interview part or after the first recruiter screening, typically there is some sort of technical challenge involved as well as a final interview with the hiring managers.

-

Screening and first interview by the recruiter

-

Technical challenge and evaluation by team

-

Interview with the Hiring Managers, Leadership Team

Even though the recruiter is most of the time involved all the way, from the very moment the need for new team members comes up until finally job offers are made and negotiated, the recruiters most significant involvement is arguably in the phase of candidate screening (including sourcing and first interview). The decisions a recruiter makes within these phases determine the face and the quality of the candidate pipeline and who gets introduced as a candidate to the rest of the team or not.

Predicting what is almost impossible to predict

Obviously, the decisions a recruiter makes need to be highly aligned with the hiring team. When it comes to alignment, there is no over-communication. But even if a recruiter is equipped with all information about the team, technologies, way of working, company, culture, etc. it would be presumptuous to claim that one could evaluate a candidate’s fit with full accuracy based on a CV (and maybe a portfolio) and a first 60 minute conversation.

Ultimately it’s anyway not about finding the “objectively” best e.g. software developers. But finding the “subjectively” best candidates of whom the Hiring Team thinks, he or she is a good addition for the team.

Worst Case Scenario

One goal of a recruiter is to facilitate the recruiting process as efficiently as possible. In terms of efficiency, a “worst case scenario” is not a candidate who gets rejected immediately after the first interview. If the recruiter’s judgement is right, a rejection after the first interview is actually one of the better case scenarios. A worst case scenario would be if a candidate goes through all recruiting steps, but in the end the parties do not come to an agreement. That means the process has a negative outcome while the maximum amount of time and effort was invested from everyone involved.

Obviously such cases can be also of tremendous value for all participants. But a case like this turns into a real worst case and a bad candidate experience if the reason for the disagreement could have been identified with relative ease from very early on (e.g. too much discrepancy between salary expectations; not enough expertise with very crucial technologies or other expertise). But at best, the process provides a pleasant learning experience which may pay out at another point in the future.

The Confusion Matrix

We have to keep in mind that there are blurred lines between a “worst case scenario” and a desirable outcome. With that being said, the overall challenge a recruiter sees him- or herself confronted with can be laid out as a problem of statistical classification, namely as a confusion or error matrix.

If we assume the recruiter is fully trusted with the responsibility of screening profiles, conducting first interviews and then deciding with whom to proceed or not, candidates can be classified into the following categories:

True positive: After the first interview, the recruiter thinks it’s a good candidate. After the team interviews, everyone agrees. Typically, you end up making those candidates a job offer. And if the candidate also has a positive impression and contractual expectations are aligned, we have a new hire!

False positive: After the first interview, the recruiter thinks it’s a good candidate. But after the team interview(s), the team disagrees. Typically, those candidates will be rejected after the second or third stage. But it also might be the case that the team is positive about the candidate but the candidate does not want to continue. There are enough reasons for both cases.

True negative: After the first interview, the recruiter thinks the candidate is not a good fit. And everyone agrees.

False negatives: After the first interview, the recruiter thinks the candidate is not a good fit. But somehow it turned out that candidate is or would have been a good fit. This is probably the most painful outcome.

True positives and True negatives are desired outcomes of a recruiter. Ending up here means you forwarded good matching candidates and you rejected those who were not. You made the right decisions.

False positive cases are not avoidable, but the ones you want to minimize. If the number of false positive cases is getting too high, it indicates that a lot of time was spent with interviews that led nowhere. Basically, the recruiter made too many ‘wrong decisions’ during the candidate screening and evaluation.

But even though one should strive to minimize the number of false positives, the truth is that this number will never be 0. If this number would be zero, it would mean that one first 60 min interview would be enough to get a full picture of the candidate.

False negative cases are especially painful, because the recruiter was not able to recognise a good candidate as such a one. Since good candidates are rare, the opportunity costs for those wrong decisions are very high. Realistically, there are always more false negative cases than one is able to identify.

Being overly cautious to avoid False negatives would lead to a rise in False positives, means increasing costs in the form of team interview time spent.

But being overly cautious to avoid False positives would lead to a rise in False negatives which would be even more costly because you missed out on a True positive. So you rather want to have more False positives than False negatives to be on the safe side.

But the only way to find the perfect balance is to improve your screening quality!

Improve your Screening Quality

There is already a countless list of articles on agile recruitment or other organisational recruitment best-practices. I do not want to repeat those but pointing out ways to improve the screening quality and mindset of the individual recruiter. Because at the end of the day, in all agile processes it is about “Individuals and Interactions Over Processes and Tools” and the mindset of “responding to change over following a plan.”

There are some obvious actions you want to take as a recruiter to improve the screening quality. Like already mentioned, there is no such thing as over-communication with the team when it comes to alignment. But often enough, there is a big hurdle which prevents the recruiter from fully grasping what exactly the hiring team is looking for and how to screen for it. And this hurdle is: Understanding of technical subject matter.

Become a better (Tech) Recruiter

In another article, I already elaborated on my journey of how I became a better (Tech) Recruiter. Even though I focussed in this article more on software engineering subject matter, the bottom line is: You don’t need to have in depth knowledge or hands-on expertise in the subject matter of the role you are recruiting for. But obviously, it can be a major advantage. Laying a solid foundation for your knowledge of software engineering or computer science in general can open up a completely new learning path into a discipline you are very familiar with on the one hand, but not at all on the other. And I promise, after you start to demystify this blackbox, recruiting will become much more fun!

Level up your technical Questions

But even if you don’t want to make a deep dive into computer science or the discipline you are recruiting for, you always want to strive for improving your screening and this goes typically along with gaining more expertise in the subject matter you are recruiting for.

In the case of recruiting for software engineering, get at least a high level understanding of e.g. software architecture, cloud computing, micro-services, software testing and development methodologies, and all the jargon you deal with on a daily basis. For consumer-friendly educational content, Youtube is my preferred search engine!

I consume tons of educational content. But if I had to recommend just one educational resources for beginners about the topic of computer science, it would be “Harvard’s CS50 - Introduction to computer science” EDX YouTube Channel. I’m sure you will find here content which will give your blurry ideas more sharpness. But in general, it’s a great resource to build foundational general knowledge. And maybe it will trigger your interest to go deeper into the rabbit hole.

Your goal is to add additional questions with a high signaling value to your repertoire. You want to be able to go beyond “How many years did you work with technology xyz?!” and you want to be able to weed out candidates who are just reciting textbook answers to eyewash you. But also, be aware that at a certain level, there is no one “K.O.-Question” which is able to draw a clear line between a good and a bad candidate. But each answer must be interpreted as a signal. But some questions are able to trigger stronger signals than other questions.

Besides watching tons of YouTube Videos, working on my own side projects, and reading articles, shadowing technical interviews and/or final interviews with hiring managers helped me a lot. Note all questions which were asked, pay attention to what the candidate answered, and ask the interviewers why exactly they asked these questions. Don’t be afraid to ask your colleagues to break the questions and everything what was said down for you in beginner friendly high-level terms. And most importantly, don’t be afraid to ask “dummy questions”. This worry of feeling exposed as a recruiter can be very real. But honesty and sincere curiosity will bring you further than “fake it till you make it”.

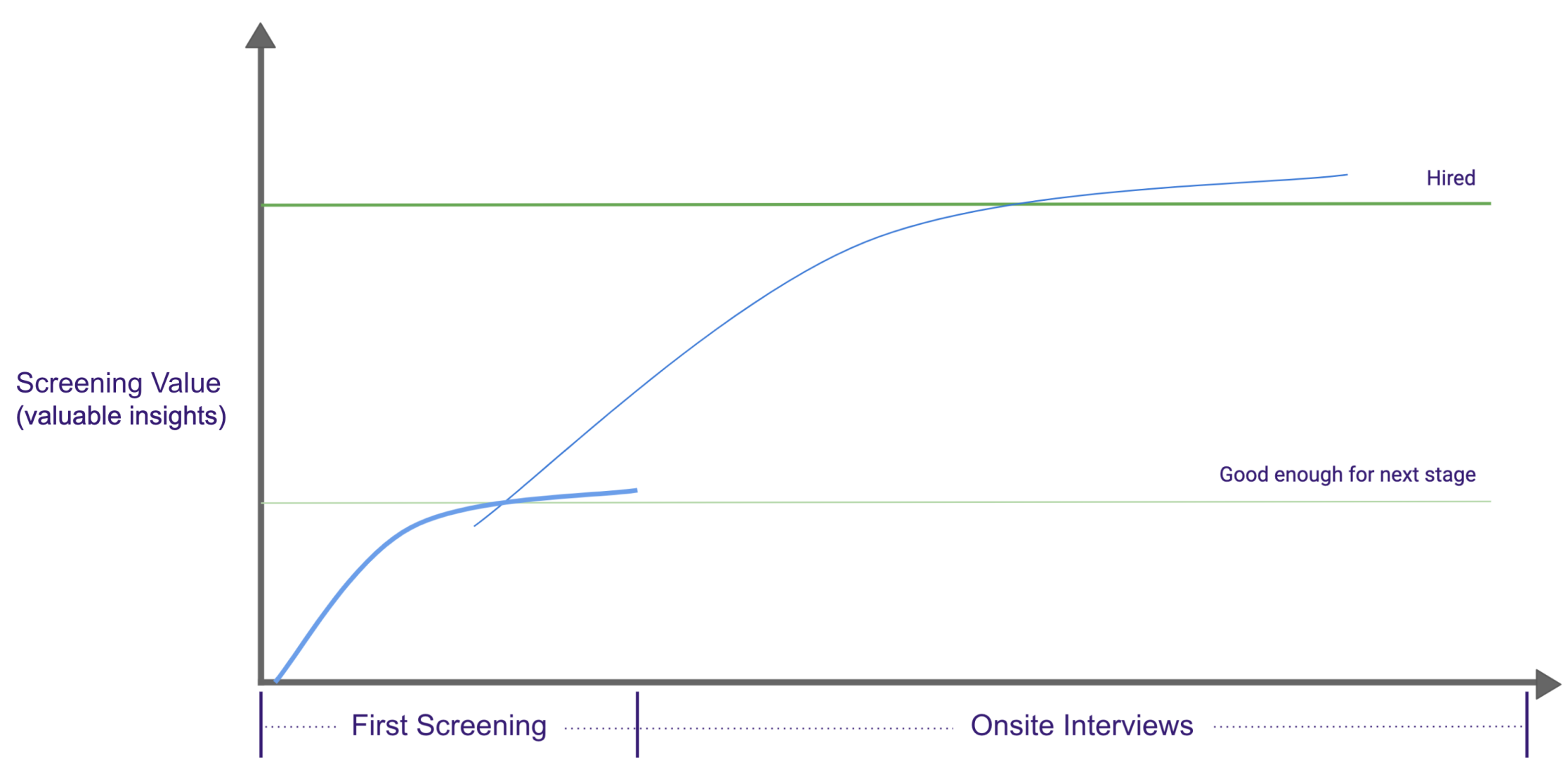

Good enough is good enough

In every interview, there is just so much you can screen or accomplish. At a certain point in the interview, the marginal screening-value of each additional question drops. That’s why it makes sense to have different interview sessions and switch gears to add new valuable insights about different skill dimensions of a candidate. But you also want to avoid overdoing it with different interview steps. You can always go deeper, but every screening step finds its saturation at some point. It very much reminds me of a golden rule in UX Design for usability testing. Same, same, but different.

Even for very experienced interviewers with extensive programming experience it’s almost impossible to make an accurate call after one single screening session. Therefore, the main goal of a first interview is not to find out how good exactly the candidate is. But to know where to draw a line for “good enough for a technical evaluation” and being able to categorize candidates accordingly. As a recruiter, you want to be able to disqualify a “bad candidate” as fast as possible. In order to screen as efficient as possible, you first want to screen for those factors which might lead to an obvious disqualification. Once you eliminate those factors, the actual tricky part of the screening starts.

As a recruiter with a non-technical background, maybe you are able to switch gears by getting more technical and thereby adding more screening-value to your session. But in the end of the day, written code tells the truth and nothing replaces a coding interview. But also here, you don’t want to overshoot the target. Overeagerly screening your candidate might hurt your team’s ability to assess and hire great candidates. Also, there is just so much you can do to sell the company to the candidate and ensure a nice candidate experience. It’s also the team that needs to do its job to sell the company.

Do not trust your gut feeling.

Recruitment is a messy business. On the one hand you want and you will improve in your screening abilities and decision making. Your confidence will rise, and rightfully so. But on the other hand there is empirical evidence that for a very significant number of your decisions, very likely you will make the wrong call. 4 out of 5 times according to Lever’s data. Your gut feeling remains a weak indicator for success when we talk about candidate evaluation.

Obviously, it’s not always the case that the candidate is not “good enough” for the company, but often enough it’s also the company that is not “good enough” for the candidate. At some point in the process, it’s out of the recruiter’s control what will happen.

From the perspective of extreme ownership, one could argue that these things should be factored into the recruiters decision-equation. But here we step into very blurry territory. Fact of the matter is, recruiting is just a messy business. And the way you are able to deal with the inevitable mess and ambiguity will determine how good of a recruiter and team member you will become.

No Mud, No Lotus

Without failure, there is no success. Both inevitably belong together, the one can’t exist without the other. Ultimately, true success is tied to the way to success. And when things go well, it’s easy to shine. But real champions show up when things get messy.

In order to really enjoy the process, you need to have an ambivalent attitude towards failure. Of course, there is nothing wrong with ambition and wanting to improve. Often enough, that means minimising the number of unsuccessful attempts and fails. But the fails themselves are not the enemy. But our inability to embrace them as a necessary part of the process and our life. Less failure does not equal more success. But our resilience and ability to endure the hard times with integrity will determine the quality of our overall success.

Even though I portray recruiting here as a statistical optimisation problem with the goal to minimise undesirable outcomes, the actual target dimension we should but we don’t optimise for is joy and happiness. But there is no machine learning algorithm which can do that for us.

At this point, I’m very skeptical when observing the trend of involving more “artificial intelligences” into the process of screening and matching jobs with candidates. If we would make a data informed decision to optimise for global happiness, dignity, and flourishment, we have to admit that we are just not able at this point to put systems like this into production and ensure a global win-win-situation. If racial-, gender-, sexual- or any other biases remain ingrained in our societal structures, technology will just amplify what it is fed with. And examples for that are ubiquitous.

I do believe in computer science as a tool for human prosperity. But not more than I believe in philosophy and ethics. When making decisions, we have the right to be wrong. But it’s our courage, integrity and the acknowledgement of our own fallibility that will determine what kind of professionals, co-workers, family-members, and human beings we are and will be.

“Try again, fail again, fail better.”